Details of DPV and References

DPV NO: 76 October 1971

Family: Potyviridae

Genus: Potyvirus

Species: Narcissus yellow stripe virus | Acronym: NYSV

Narcissus yellow stripe virus

A. A. Brunt Glasshouse Crops Research Institute, Littlehampton, Sussex, England

Contents

- Introduction

- Main Diseases

- Geographical Distribution

- Host Range and Symptomatology

- Strains

- Transmission by Vectors

- Transmission through Seed

- Transmission by Grafting

- Transmission by Dodder

- Serology

- Nucleic Acid Hybridization

- Relationships

- Stability in Sap

- Purification

- Properties of Particles

- Particle Structure

- Particle Composition

- Properties of Infective Nucleic Acid

- Molecular Structure

- Genome Properties

- Satellite

- Relations with Cells and Tissues

- Ecology and Control

- Notes

- Acknowledgements

- Figures

- References

Introduction

- Described by Darlington (1908) and Haasis (1939).

- Selected synonyms

- Narcissus ‘greys’ virus (Rev. appl. Mycol. 8: 311)

- Narcissus mosaic virus (Rev. appl. Mycol. 7: 784), but not now recommended (see Notes).

- Narcissus mosaic virus (Rev. appl. Mycol. 7: 784), but not now recommended (see Notes).

- A virus with flexuous filamentous particles c. 12 x 755 nm. Transmissible by inoculation of sap and by nine aphid species in the non-persistent manner. It occurs naturally only in members of the Amaryllidaceae, but its distribution is world-wide. A typical, but apparently distinct, member of the potato virus Y group.

Main Diseases

Causes mosaic diseases of daffodils, jonquils and nerines. Infected plants of most daffodil cultivars show conspicuous chlorotic stripes on leaves (Fig. 1) and flower stalks, ‘broken’ flowers (Fig. 3), reduced bulb size and, eventually, severe stunting; the chlorosis in some cultivars is less conspicuous (Caldwell & Kissick, 1950), and the cv. Magnificence usually develops only green stripes (Brunt, 1968).

Geographical Distribution

World-wide, especially in temperate regions.

Host Range and Symptomatology

Natural host range apparently restricted to a few members of the Amaryllidaceae, but the virus can infect one member of the Aizoaceae.

- Diagnostic species

- Narcissus pseudonarcissus

(daffodil). Conspicuous chlorotic stripes on leaves in early spring, but symptoms produced at higher ambient temperatures are less severe; chlorotic areas often raised and roughened (Caldwell & James, 1938). Flowers often of poor quality, and sometimes ‘broken’. Plants infected early in the season by aphid transfer or inoculation of sap may produce symptoms within 4 months, but plants infected later rarely produce symptoms within 15 months. - Narcissus jonquilla (jonquil). Narrow chlorotic stripes, in some areas

coalescing to produce almost complete chlorosis. Flowers may be broken (Fig. 3).

- Nerine bowdenii (nerine). Symptoms essentially similar to but sometimes less severe than those induced in daffodils (Fig. 2).

- Tetragonia expansa. A few chlorotic local lesions after 10-14 days, enlarging to 6-9 mm in diameter after 28 days (Fig. 4); unreliable during summer months.

- Nerine bowdenii (nerine). Symptoms essentially similar to but sometimes less severe than those induced in daffodils (Fig. 2).

- Propagation species

- Narcissus pseudonarcissus

and N. jonquilla are both suitable for maintaining the virus and are good sources of virus for purification; Tetragonia expansa is also useful.- Assay species

- N. pseudonarcissus:

by recording the proportion of inoculated plants becoming infected. Tetragonia expansa is useful for local lesion assays during winter.

Strains

None reported.

Transmission by Vectors

Transmitted by 9 aphid species, including Aphis fabae, Acyrthosiphon pisum and Macrosiphum euphorbiae (Blanton & Haasis, 1939, 1942), but not by Myzus persicae (van Slogteren & de Bruyn Ouhoter, 1946). All instars can transmit; virus is acquired within 2-5 min and inoculated within 5-10 min. No latent period.

Transmission through Seed

Not seed- or pollen-borne (Haasis, 1939; Caldwell, 1946).

Transmission by Dodder

None recorded.

Serology

The virus is a moderately good immunogen; antisera with titres of 1/5000 have been produced by injecting rabbits intravenously with partially purified virus 9 times within 12 days (D. H. M. van Slogteren, unpublished). Antisera react in tube precipitin tests to produce flagellar precipitates, but the microprecipitin test is more sensitive (van Slogteren, 1955). Antibodies conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate have been used to locate virus within infected cells (Cremer & van der Veken, 1964).

Relationships

The virus has properties typical of members of the potato virus Y group, but is not serologically related to carnation vein mottle, bulbous iris mosaic, hippeastrum mosaic, hyacinth mosaic, pepper veinal mottle, potato Y, turnip mosaic or bean yellow mosaic viruses (van Slogteren, 1955; Brunt, unpublished) nor to two other viruses from narcissus, narcissus white streak virus (van Slogteren, 1955) and narcissus degeneration virus (a newly recognised virus prevalent in N. tazetta cv. Grand Soleil d’Or).

Stability in Sap

In daffodil sap, the thermal inactivation point (10 min) is 70-75°C, dilution end-point 10-2 to 10-3 and infectivity is retained at 21-24°C for c. 72 hr (Haasis, 1939).

Purification

Two methods have proved useful:

1. Cremer & van der Veken (1964). Shred and lyophilize infected daffodil leaves, and extract with chloroform, ethanol, acetone and ether, retaining the powdered residue after each extraction. Disperse the powder derived from each 1 g of leaf tissue in 90 ml 0.067 M phosphate buffer at pH 7.2 containing 0.3% (v/v) potassium cyanide and 0.3% sodium sulphite. Precipitate virus from the fluid by adding ammonium sulphate to 66% (w/v), resuspend in water, dialyse exhaustively and clarify by brief low speed centrifugation.

2. Brunt (unpublished). Homogenize infected leaves of daffodil or Tetragonia expansa (1 g leaf to 3 ml extractant) in 0.1 M borate buffer containing 0.2% (v/v) thioglycollic acid and 0.05 M disodium ethylene diamine tetraacetate (pH 8.0). Shake the fluid for 1 hr with 25% (v/v) chloroform, centrifuge at 10,000 g for 15-20 min, and sediment virus from the aqueous phase by centrifugation at 78,500 g for 90 min. Resuspend in 0.05 M neutral borate buffer, remove insoluble material by low speed centrifugation, and either repeat the cycle of differential centrifugation, or centrifuge in 10-40% sucrose density gradients. Recover the virus from the specific light-scattering zone by dialysis followed by differential centrifugation.

Properties of Particles

No reports.

Particle Structure

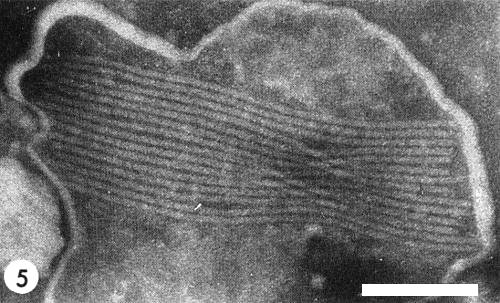

The virus particles are flexuous filaments c. 12 x 755 nm (Fig. 5) which, in sap mixed with 2% phosphotungstate, sometimes occur in aggregates bounded by a membrane (Brunt & Atkey, 1967).

Particle Composition

Unknown.

Relations with Cells and Tissues

The raised and roughened chlorotic surfaces of infected narcissus leaves result from the abnormal division and growth of parenchyma cells which eventually rupture the overlying epidermis (Caldwell & James, 1938). Cremer & van der Veken (1964) found virus throughout the cytoplasm, but not within the nuclei, of all narcissus tissues; they also found numerous pinwheel inclusions (Fig. 6) within infected cells, but were unable to confirm earlier reports (McWhorter, 1935; Caldwell & James, 1938) of amoeboid intracellular inclusions.

Notes

The name ‘narcissus mosaic virus’ was commonly used in USA (McWhorter, 1935; Haasis, 1939) and occasionally in UK (Caldwell, 1946) as a synonym for narcissus yellow stripe virus, but was also used in the Netherlands for another virus (van Slogteren & de Bruyn Ouboter, 1946; van Slogteren, 1955; Cremer & van der Veken, 1964) which was later shown to be a typical but distinct member of the potato virus X group (Brunt, 1966). Further confusion can be avoided if the name narcissus mosaic is now used only for the latter virus. ‘Narcissus greys virus’ is also an unsatisfactory synonym, because of possible confusion with narcissus white streak virus (Moore, 1949).

In N. Europe narcissus yellow stripe virus spreads slowly (Hawker, 1943) because apterous aphids rarely colonise daffodils, and migratory alatae are usually present for only 4-8 weeks before plants senesce (Broadbent, Green & Walker, 1962). Nevertheless, it is probably the most damaging of the thirteen viruses known to infect narcissus; two of these, narcissus white streak virus and narcissus degeneration virus, have particles similar in size and shape to those of narcissus yellow stripe virus, but induce different diseases and are serologically distinct (Brunt, 1970). Of the remaining viruses, narcissus mosaic and narcissus latent occur naturally only in daffodils, and jonquil mild mosaic only in jonquils, but seven others (cucumber mosaic, tobacco rattle, tobacco ringspot, arabis mosaic, strawberry latent ringspot, raspberry ringspot and tomato black ring) have extensive host ranges and are readily isolated and identified.

Figures

References list for DPV: Narcissus yellow stripe virus (76)

- Blanton & Haasis, J. econ. Ent. 32: 469, 1939.

- Blanton & Haasis, J. agric. Res. 65: 413, 1942.

- Broadbent, Green & Walker, Daffodil Tulip Yb. 28: 1, 1962.

- Brunt, Ann. appl. Biol. 58: 13, 1966.

- Brunt, Rep. Glasshouse Crops Res. Inst. 1967: 102, 1968.

- Brunt, Daffodil Tulip Yb. 36: 18, 1970.

- Brunt & Atkey, Rep. Glasshouse Crops Res. Inst. 1966: 155, 1967.

- Caldwell, Nature, Lond. 158: 735, 1946.

- Caldwell & James, Ann. appl. Biol. 25: 244, 1938.

- Caldwell & Kissick, Daffodil Tulip Yb. 16: 63, 1950.

- Cremer & van der Veken, Neth. J. Pl. Path. 70: 105, 1964.

- Darlington, Jl R. hort. Soc. 34: 161, 1908.

- Haasis, Mem. Cornell Univ. agric. Exp. Stn 224: 22 pp., 1939.

- Hawker, Ann. appl. Biol. 30: 184, 1943.

- McWhorter, Phytopathology 25: 896, 1935.

- Moore, Bull. Minist. Agric. Fish Fd, Lond. 117: 78, 1949.

- van Slogteren, Ann. appl. Biol. 42: 122, 1955.

- van Slogteren & de Bruyn Ouboter, Daffodil Tulip Yb. 12: 3, 1946.